So Long, Suckers! Creature Most Likely to Colonise Earth After Humans Die Out is…an OCTOPUS

Forget planet of the apes.

The animal most likely to take over from humans and become the dominant species on Planet Earth is…an octopus.

Professor Tim Coulson of the University of Oxford, one of the world’s leading zoologists and biologists, said the cephalopods are in “pole position” to colonise the world in the event humanity dies out.

The marine invertebrates possess the physical and mental attributes necessary to evolve into the next civilisation-building species, he said.

Their “dexterity, curiosity, ability to communicate with each other, and supreme intelligence” means they could create complex tools to build a vast Atlantis-like civilisation underwater.

Professor Coulson, who has also advised governments, said the predators – which can breathe for 30 minutes out of water – are unlikely to fully adapt into land animals.

But over millions of years, they might develop their own methods of hunting on land in much the same way as humans have done at sea.

This may include SCUBA-like breathing gear to extend the time they can remain out of the water, he said.

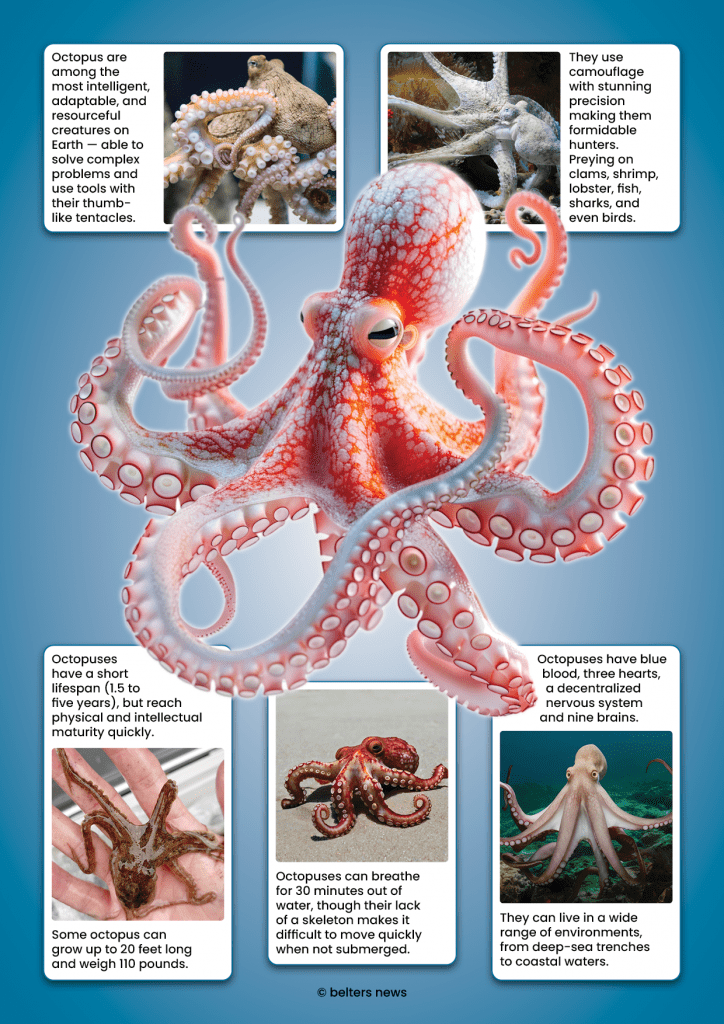

Speaking to The European magazine, Professor Coulson, who was previously Professor of Population Biology at Imperial College London and held positions at Cambridge University and the Institute of Zoology London, said: “Octopuses are among the most intelligent, adaptable, and resourceful creatures on Earth.

“Their ability to solve complex problems, manipulate objects, and even camouflage themselves with stunning precision suggests that, given the right environmental conditions, they could evolve into a civilisation-building species following the extinction of humans.

“Their advanced neural structure, decentralized nervous system, and remarkable problem-solving skills make octopuses uniquely suited for an unpredictable world.

“These qualities could allow them to exploit new niches and adapt to a changing planet, especially in the absence of human influence.

“In a world where mammals dominate, octopuses remain an underappreciated contender. Their advanced cognition, tool-use, and ability to adapt to changing environments provide a blueprint for what might emerge as the planet’s next intelligent species after humans.”

Professor Coulson has awards from major institutions including the Royal Society, is the former editor of several science journals, and has published more than 200 peer-reviewed articles with a focus on complex biological systems.

His latest book, The Universal History of Us: a 13.8-billion-year tale from the Big Bang to You, focuses on what had to happen since the universe’s birth for humans to exist.

He added: “Of course, the rise of the octopuses is all speculative: evolution is unpredictable, and we can’t say with certainty what path it will take in the event of human extinction.

“The future of life on Earth is shaped by countless variables, and any number of species could rise to prominence. That said, given the octopus’s remarkable intelligence, adaptability, and diverse range of survival strategies, it wouldn’t be the most far-fetched bet to imagine them thriving in a post-human world.”

If humans were to die out, perhaps through wars or climate change, most scientists agree that the creature to ‘replace’ us would need to be dextrous.

Without dexterity, a species would be unable to develop complex tools to modify their environment and colonise the planet in the way that man has done.

Some birds, such as crows, ravens, and parrots, for example, are extremely intelligent and construct communal nesting sites that can last for decades.

Several insect species build complex towering structures, which bear a resemblance to human civilisation.

But neither birds nor insects are likely to fill the ecological role previously held by humans because they lack the dexterity of humans and octopuses.

Primates have long been considered the natural forerunner of civilisation because of their capacity to manipulate objects.

Hominids like chimps and bonobos are smart, have opposable thumbs, already use tools, and can walk on two legs like humans.

But primates would likely face extinction alongside humans because they are vulnerable to the same threats that affect us.

Even if they did survive, primates are vulnerable to predators and competition, are limited in terms of the environments and ecosystems in which they can live, and have slow reproductive rates and development.

Primates also rely on tight-knit communities for survival – with coordinated social behaviours like hunting, grooming, and defence against predators – and their small population sizes mean they might struggle to adapt to a changed world.

“Octopuses, on the other hand, are a potentially better candidate for filling an ecological niche in a post-human world,” Professor Coulson said.

They can already differentiate between real and virtual objects, solve puzzles, manipulate their surroundings, use complex tools using their thumb-like tentacles, and live in a diverse range of environments from deep-sea trenches to coastal waters.

Octopuses – not ‘octopi’ – are also adept at surviving in harsh conditions and are formidable hunters with a wide variety of prey including clams, shrimp, lobsters, fish, sharks and even birds.

Though they have relatively short lifespans, from between 1.5 to five years, they reproduce and reach physical and intellectual maturity very quickly.

And while they can be sociable creatures, octopuses fend largely for themselves and do not rely on strict, coordinated social behaviours like primates do.

Professor Coulson said the invertebrates are unlikely to evolve into land-based animals because of their lack of a skeleton, which means they struggle to move quickly and easily when out of water.

But he said the creatures – some of which grow to 20ft and weigh 110 pounds – could conceivably build underwater cities and towns akin to those we recognise on land.

Thanks to evolution, it is “possible, if not probable” that they could develop their own methods of breathing out of water and hunt prey like deer, sheep and other mammals on land.

Professor Coulson said: “It’s important to remember that these are just possibilities, and that it’s impossible to predict with any degree of certainty how evolution will unfold over extended periods.

“Random mutations, unforeseen extinction events, and population bottlenecks can all significantly influence the trajectory of evolution, making it challenging to determine whether another species will develop human-level intelligence or the inclination to construct cities.

“But could octopuses replace humans – and potentially also primates – if they were to die out? Absolutely.

“Would octopuses build vast underwater cities and come onto land wearing breathing apparatus to shoot a deer? We’ve no way of knowing. But we certainly can’t rule it out.

“Humans learned to catch fish and to navigate over and under water, so it is also possible, if not probable, that octopuses might do the same on land.”